In 1933, the mainstream conservative political party invited Adolf Hitler to become chancellor of Germany in a cynical ploy to stay in power. The conservatives knew that Hitler was a danger to Germany’s fragile democracy. They didn’t care.

The conservatives claimed that Hitler didn’t really intend to abolish all independent power bases in Germany, starting with journalists and government departments. They said Hitler didn’t mean it when he threatened retribution against his enemies. (Immediately after coming to power, Hitler ordered the arrest of the attorney who had prosecuted him for tax evasion years earlier. He also filed bogus criminal charges against a prominent newspaper that was critical of his policies, forcing the paper to close.) They also claimed that Hitler wasn’t serious about eliminating the Jews in Germany and Europe.

But not everyone was so willfully stupid or greedy for power. Some people believed Hitler meant what he said. One such clear-eyed individual was Anna Essinger.

Anna Essinger

Anna was born in Ulm, Germany in 1879 into a family of prosperous, assimilated Jews. At the age of 19, Anna joined a widowed aunt in Nashville, Tennessee, then moved to Wisconsin to attend college. She was studying for her doctorate at the University of Wisconsin when World War I began in 1914 and anti-German sentiment forced her return to Germany.

While in the U.S., Anna had become acquainted with several influential Quakers. She melded their humanitarian and compassionate values with her belief that education is the key to progress. In 1926, she started a school at Herrlingen (now Blaustein), Germany.

The Herrlingen school was unlike anything ever seen before in Germany. The school looked like a private home and many classes were held outdoors. The curriculum emphasized art and music. The only rules were to be honest, hard-working, to resolve conflicts peacefully, and to treat others fairly. Misbehaving students were sent to Tante (Aunt) Anna for a compassionate chat about how their bad behavior affected others.

For several years, the school flourished as Jewish and non-Jewish parents looked for an alternative to the typical regimen of corporal punishment and rote learning. That changed as the Nazis gained political power in the Reichstag and began gaining control of local and state governments. An early target was education and school curricula.

Adolf Hitler at the Nuremberg Rally

Local Nazi bigwigs threatened to close the school unless Anna taught a curriculum approved by the Nazis which emphasized obedience to the state, glorification of the military, and “history” lessons blaming Jews for everything wrong in Germany and the world. Then they ordered all non-Jewish staff and students to leave the school. Tante Anna knew it was a matter of time before the Nazis forced the school to close.

Anna decided to save her school from the Nazis. She masterminded an audacious plan to move the school to England with the help of Quaker acquaintances. The logistics were a nightmare, requiring travel documents and permissions from multiple levels of government in Nazi Germany and the countries they would travel through. Parents had to consent to send their children to England with no promise that they would ever meet again.

In the summer of 1933, she put her plan in motion using a cover story that they were taking an educational school trip. School trips during the summer break were popular in the 1930’s as part of the “wanderlust” movement, in which students and young adults traveled around Europe to visit cultural sites and experience local cultures. The wealthier ones could even afford to travel to the U.S.

Tante Anna’s students were split into three groups accompanied by their remaining teachers. Each group left from the local train station but took a different route over the following week. The cover story was that they would take a two-week educational holiday before returning to Herrlingen. Instead, the groups met up at the Belgian port city of Ostend and boarded a boat to England.

The school resettled into a rundown manor house called Bunce Court in Kent, England. Anna immediately embarked on a never-ending struggle to scrape together enough money to pay the rent each month and buy food. Most of the teachers were refugee Jews who received room and board in lieu of a salary.

Anna’s optimism inspired everyone. Under the supervision of a teacher, students in the woodworking shop churned out materials needed to repair the manor house and outbuildings. Other students assisted the handyman who maintained the boiler that provided heat and hot water. The most popular duty was assisting in the kitchen since that often meant getting a little extra food.

The school was soon self-sustaining as the students planted a huge vegetable garden and raised pigs. They later added beehives and sold the honey. It wasn’t all hard work. The former lawns were transformed into a swimming pool, an outdoor amphitheater, and a football (soccer) pitch. Classes were held outside whenever the weather permitted.

Meanwhile, the lives of their parents in Germany were increasingly hopeless. Jews seeking to emigrate were forced to sign over all their assets to the Nazis as the price for leaving Germany. But they also needed to find a country willing to take them, which was nearly impossible since they would be destitute upon arrival.

In June 1938, England and the U.S. headlined a conference at Evian, France to discuss waiving immigration quotas to allow German Jews to emigrate. But the conference quickly fizzled into nothing. Americans were isolationist and anti-immigrant. Politicians of all stripes claimed that Jewish immigrants would be a burden on taxpayers.

The indifference of democratic countries encouraged the Nazis to ramp up their activities. In November 1938, they stage-managed the destruction of Kristallnacht, blamed the Jews for the violence, and stripped the Jews of their citizenship. Anna’s brother was forced to hand over the family’s furniture business to a Nazi-approved goon, who quickly bankrupted the company.

The children at Bunce Court learned about the struggles of their parents and siblings from letters they received. Mail delivery between England and Germany continued until war was declared on September 1, 1939. After that, the Red Cross and other private organizations attempted to pass along information.

The children were never able to reunite with their parents, who perished in the Holocaust. After the war, Tante Anna spent many hours working with Jewish refugee organizations and the Red Cross trying to locate relatives of the children but was rarely successful.

The Herrlingen school building was confiscated by the Nazis. It was later gifted to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel as a reward for military service. (He had already collected every possible military decoration.) Rommel was living at the former school when he was forced to commit suicide in October 1944. The building is now a museum for both Rommel and Anna Essinger.

Most people, when faced with dictators and evil, will concede without a whimper engaging in “anticipatory obedience”, a term coined by Professor Timothy Snyder. Anna Essinger is one of a very rare breed of people who refused to give in to evil or to allow a world without hope.

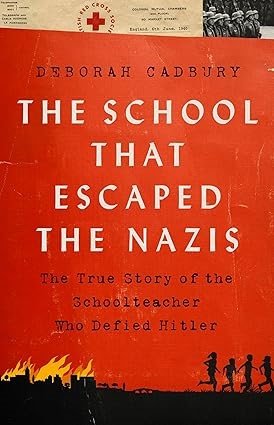

To learn more about this remarkable woman and her school, see The School That Escaped the Nazis, by Deborah Cadbury (2022)