Lucretia Mott was barely five feet tall, weighed less than 100 pounds and she scared the hell out of men. She believed that slavery was morally repugnant and should be abolished. She also believed women should have equal rights with men, including the right to vote. Men feared her because she was a powerful and persuasive public speaker.

Lucretia Mott was doubly dangerous because she was an organizer. In 1833, she and other Quaker women founded the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. The new group immediately caused a scandal because (gasp!) black women, like the poet Sarah Forten, were full members. Most abolitionist groups either banned African Americans or offered them second-class membership.

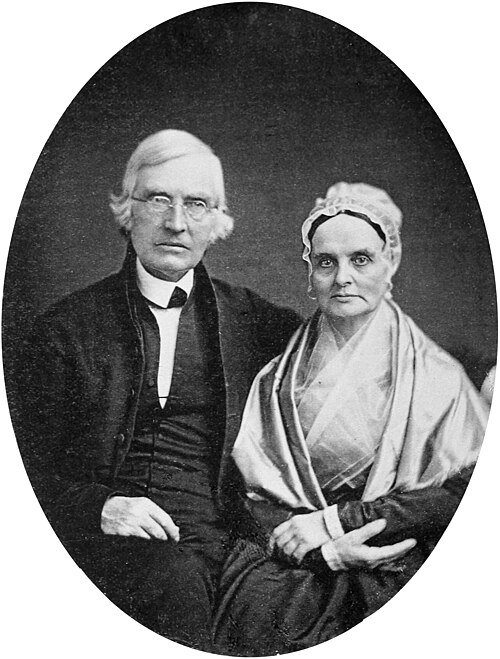

Lucretia and James Mott

The women’s group was formed in response to the American Anti-Slavery Society which was also founded in Philadelphia. This group was dominated by men who ignored the suggestions of women during the debate over the content of the group’s constitution. Their dismissive attitude didn’t stop Lucretia from repeatedly interrupting the debate to offer her own suggestions. The women were also denied the right to sign the society’s constitution.

The women’s group was immediately attacked in newspaper editorials. Many editorials ordered them to stop poking their noses into politics and to return to their “domestic duties” as wives and mothers. Other editorials attacked them for mixing races, which was an affront to almost all white Americans at that time. Some editorials worried (correctly) that women would use the abolition movement as a starting point to argue for women’s rights, most importantly, the right to vote.

Underlying all the criticism was an amorphous fear that equality for women was a threat to men. Lucretia Mott was fortunate in having a husband, James, who supported her political organizing. Most of the women in the early abolitionist movement had to maneuver around their husbands’ disapproval or they were unmarried women.

Since women couldn’t express their opinion through their votes, they had to find other methods for getting their abolitionist message in front of Congress. They chose to petition. Today, petitions constantly circulate on social media with a plea to readers to “sign” the petition, an effort of dubious value since there is no way to verify these electronic signatures. The abolitionists did it the old-fashioned way; they trudged from town to town, clutching a paper copy of their petition and asking everyone they met to sign it.

It was dangerous and dirty work. One society’s report called it “weary work”. Men yelled abuse at the women, claiming they had no right to be involved in politics and accusing them of sedition. The women were often spit upon and constantly ridiculed. One woman stated that they weren’t just fighting to end slavery, “we must also overthrow the injurious prejudices relative to the real duties and responsibilities of women”.

Many of the canvassers were teenage girls as young as 11 years old. They were taught a script, which included handling hostile responses. Their motto was “Let no frown deter, no repulses baffle. Explain, discuss, argue, persuade”. One of these teenage volunteers was Susan B. Anthony. She later used the skills she had honed during the petition drives to fight for the right to vote.

One of the earliest petition drives was organized by Lucretia Mott. By 1835, petitions calling for an end to slavery were flooding the halls of Congress, outraging Southern slave owners and their northern sympathizers, many of whom were merchants profiting from sales to southern states or manufacturers who bought slave-produced goods like cotten.

Sen. John C. Calhoun

Sen. John C. Calhoun (South Carolina) had already led an effort to ban the U.S. Mail from delivering abolitionist newspapers and pamphlets in slave states. Another South Carolinian, Rep. James Hammond proclaimed that abolitionists should be punished with “terror - death” and demanded that Congress should reject any additional abolitionist petitions. For politicians, censoring speech they didn’t like became an obsession.

Rep. James Hammond

A gag law was passed by the House of Representatives which prohibited members of the House from reading or discussing the petitions and from referring them to committees. Committees are the basis upon which Congress acts, gathering information and drafting new laws. If no committee could review the petitions, the petitions were essentially toilet paper.

The Senate never passed the gag law, but they routinely ignored the petitions that flowed in from the folks back home. Both houses of Congress appeared indifferent to the concerns of their constituents and out of touch (particularly with women who couldn’t vote despite being half the population).

Even people opposed to abolishing slavery worried that Congress was destroying the constitutional liberties of Americans by censoring speech. If Congress could arbitrarily decide what kinds of speech were safe or dangerous, then “farewell, a long farewell to our freedom,” opined The Evening Post of New York. The criticism caused many Northern state legislatures to abandon efforts to pass state censorship laws.

The gag law turned out to be a spectacular recruiting tool for abolitionists. Women flocked to the abolitionist societies and volunteered to canvass communities with new petitions. The abuse and ridicule they suffered energized the women’s rights movement.

In 1848, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other women met at Senaca Falls, New York for a convention on women’s rights. They demanded civil rights, including the right to own property in their own name, the right to an education, and most crucially, the right to vote. Women finally won the right to vote in 1920 when the 19th Amendment was ratified.

The petition drives of the 1830’s demonstrate that a reactionary and out-of-touch government cannot ignore social justice issues forever. Social (and political) reform is a long game, measured in years and sometimes decades. Eventually repressive governments collapse under the weight of their own hypocrisy and corruption. But this can only happen when citizens are sufficiently motivated to fight for their own interests by resisting political and social injustices. Resistance begins by registering and then voting in every election at all levels of government.

This account of women abolitionists who became suffragists is based on The Republic of Violence, by J.D. Dickey (2022).

If you would like Norma’s blog sent to your inbox, we invite you sign up by clicking here! And we will see you next time!

And be sure to follow Norma on LinkedIn