Anna Essinger was a force of nature. Her optimism kept her moving forward against crushing challenges. She was born in Ulm, Germany in 1879 into a family of prosperous, assimilated Jews. In 1926, she started a school at Herrlingen (now Blaustein), Germany. She was known to her students as Tante (Aunt) Anna.

In 1933, she organized the transfer of the school’s Jewish students and teachers to England to protect them from the Nazis. [See November 2025 blog.] The school resettled into a rundown manor house in Kent, England, called Bunce Court. Since there was no money to pay for repairs, the students and staff renovated the property and transformed it into a sort of friendly Hogwarts. The students worked in rotating teams that repaired the buildings, tended a vegetable garden and beehives, and raised chickens and pigs.

Anna Essinger

During the war, many of the children worked on neighboring farms to supplement the school’s finances and to obtain more food. The school also accepted local English children as required by the local school board as the price for obtaining the necessary permits to operate as a school. Their tuition provided additional financial support for the school.

The majority of students at any given time were Jewish refugees who arrived in several phases. Each group had specific psychological and emotional problems based on their wartime experiences. The first group were the original refugees from Herrlingen. They had suffered the least emotional damage because they escaped Germany before persecution of the Jews had ramped up.

The next group were Kindertransport children who arrived between December 1938 and September 1939. Tante Anna coordinated with the Refugee Children’s Movement which organized the Kindertransport trains. Children could only gain a seat on a Kindertransport train if someone paid for their passage (essentially a ransom) and there was a family, preferably Jewish, who would foster them when they arrived in England.

Kindertransport children arriving in England

Most of the Kindertransport children were from assimilated Jewish families. That didn’t matter to a rabbi who delayed one trainload of children in Germany because, in his opinion, there weren’t enough Orthodox Jewish families among the volunteer foster parents.

In early 1939, England appealed to the U.S. to allow 20,000 Jewish refugee children into the U.S. The proposed legislation needed to waive the severe limits on legal immigration stalled in Congress. One idiotic and unidentified member of Congress argued that “admitting children without their parents was against God’s law”.

Some of the Kindertransport children arrived at Bunce Court. Unlike the children who fled in 1933, these children were deeply traumatized. They had been subjected every day to casual brutality and then witnessed the looting and murders during Kristallnacht. Today, these children would be diagnosed with PTSD. In 1939, Anna and her staff helped these children learn to have hope again through music, art, gardening, and caring for the farm animals.

Bunce Court

Then, more financial bad news hit the school. In 1939, the owner of Bunce Court informed Anna that the school’s lease would not be renewed. The property was valued at £5,000 (equivalent to $513,222 today), an impossible sum. A lesser person would have folded at the knees. Anna refused to give up. She decided to hold a fundraiser.

In June 1939, the school staged The Magic Flute for the local community and their patrons. Additional money was raised from the sale of the students’ art and handicrafts. The Dean of Canterbury Cathedral was so impressed, he invited the students to restage their production at the cathedral. Anna raised enough money to convince the School Council (her board of directors) that they could obtain a mortgage to buy Bunce Court. The school was saved again.

But the hits kept coming. In June 1940, Bunce Court was requisitioned for use as an RAF base and the school was given three days to evacuate. While students and staff packed up the school, Anna traveled to the west of England and found another rundown estate called Trench Hall. In the space of three days, Anna signed the lease, hired buses and trucks to move their belongings, and arranged for the youngest children to temporarily stay at another school. The school took another financial hit when they had to abandon their chickens, pigs, beehives and vegetable garden at Bunce Court.

Trench Hall had no electricity, no plumbing, a leaky roof, and a lack of space. In the first few weeks, the staff stayed up all night operating a hand pump to provide enough water for everyone the following morning. The students immediately got busy repairing the buildings. Soon, the older boys were sleeping in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Garages and the Saddler’s Shoppe. Teachers slept in renovated horse stalls. A sunken rose garden was converted into an open-air theater.

While operating at Trench Hall, the school received a third wave of students, Kindertransport children who had been living in English foster homes. These children were traumatized while living in Nazi-occupied countries and then again by foster families who had no idea how to cope with their emotional problems ranging from food hoarding to nightmares to angry outbursts.

When the war ended, the school returned to Bunce Court. They found the place completely trashed by the RAF. Tante Anna didn’t hesitate and neither did her students, who were old hands by now at fixing up uninhabitable spaces. They repaired the buildings and planted a new vegetable garden.

While these repairs were being made, Bunce Court received a fourth and final wave of students. These students were known as the “concentration camp boys” because they had survived the camps or by living rough in the Polish countryside. (Girls were less likely to survive because the Nazis classified them as “useless eaters” to be murdered immediately.) These deeply traumatized survivors were each adopted by a group of their fellow students who helped them to “become human again”, as one survivor put it.

The refugee children of Bunce Court ended the war as orphans. Tante Anna coordinated with the Red Cross and Jewish refugee organizations to trace the families of her students. The parents and most of the extended families of the children had perished in the Holocaust.

About 900 students passed through the school before Bunce Court closed in 1948. Most of them became college graduates and leaders in their professions. A few of the students never recovered from their childhood trauma, leaving a trail of depression, broken marriages, and substance abuse that affected their own children. However, they never forgot the kindness and caring of Tante Anna and stayed in touch with her until her death in 1960.

Today, Bunce Court is divided into four apartments. A resident became interested in the history of the building after talking to several people who showed up to look at the house. The visitors were former students or the children and grandchildren of students.

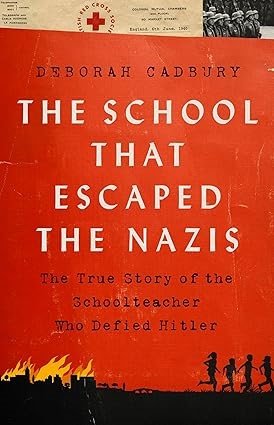

Anna Essinger is one of a very rare breed of people who refuse to allow a world without hope. To learn more about this remarkable woman and her school, see The School That Escaped the Nazis, by Deborah Cadbury (2022)