For ten long years, the workers had fought for improved working conditions. They wanted an 8-hour workday, a shorter workweek, increased attention to worker safety, and to be treated with respect as human beings.

Their demands were met with police truncheons and militia, the private armies hired by the factory owners. National Guard troops were often activated by governors who owed their political office to the people with the money.

The madder the workers got, the more scared the employers became and the more extreme their reactions. As union membership expanded, employers hired spies to infiltrate the organized labor movement. Union organizers lost their jobs, were frequently arrested on dubious charges, or turned up dead. Employers locked out union workers, then brought in strikebreakers, who were protected by Pinkerton agents that had been temporarily sworn in as sheriff’s deputies.

On May 4, 1886, some workers gathered for another labor rally in Haymarket Square in Chicago. As the speechifying began, a bomb was thrown at the police forming a perimeter around the crowd. The police responded by blasting away with live ammo. In the aftermath, seven policemen and four civilians lay dead. Uncounted numbers were injured.

Although no one was ever conclusively identified as the bomber, eight individuals were charged with murder. A quick trial in August 1886 resulted in convictions and eventually four were hanged. Newspapers sympathetic to workers published images of gallows and nooses next to sketches of the “martyrs”. Newspapers sympathetic to the factory owners branded labor unions and workers as “anarchists”.

Anarchy was a muddled middle-class political philosophy projected onto the labor movement. The middle class then, as now, was a sandwich being squeezed from above by aristocrats and fabulously wealthy industrialists and from below by the growing masses of urban factory workers. The middle-class could never become aristocrats like the Crawley family at Downton Abbey and they lacked the resources to become factory owners. But they could slide down into the ignominy of poverty. They felt that they were not reaping the benefits of Gilded Age capitalism.

Anarchy was initially defined by individuals like Prince Peter Kropotkin, a Russian aristocrat with a first-rate education and a gift for gab. He developed “white guilt” at the privileges enjoyed by his social class while most Russians were still serfs, essentially slaves to the aristocrats who owned the land worked by the serfs. Tsar Alexander II decreed an end to serfdom in the 1860’s only to be assassinated by an anarchist in 1881. His son, Tsar Alexander III, reacted much like Stalin or Putin, imprisoning and torturing anyone even vaguely suspected of dissent.

Prince Peter Kropotkin

Kropotkin fled Russia to evade a one-way trip to a Siberian prison. He went to Switzerland where he made fiery speeches advocating the overthrow of the capitalist system. Kropotkin preached that society could only survive if the bourgeois world was destroyed. Bourgeois intellectuals and college students packed the halls where he spoke.

As support grew, so did the inevitable backlash. No one has ever willingly given up a single privilege, particularly when there is a financial penalty, say higher taxes, attached to such a sacrifice. Besides, the anarchists couldn’t offer an economic system that would be fairer to everyone. Those who saw benefits in capitalism decided that Switzerland would be better without the gabby Russian.

The Swiss government expelled Kropotkin, so he went to Paris, where he promptly engaged in dubious activities leading to his arrest. In exchange for a pardon, he agreed to leave France. He went to England, which has a long tradition of tolerating political refugees and oddballs.

But while Kropotkin and his friends enjoyed their gabfests, they had no idea what life was really like for the “victims of capitalism”. In Chicago, the workers who met in Haymarket Square led an almost unimaginably grim life. They worked 10 hours a day, six days a week, with no paid leave and no retirement plan. They made about $1.50 a day (about $50 a day at today’s rates). A worker injured on the job or who was no longer physically able to do the job found himself unemployed. A worker killed on the job left behind a destitute family who faced homelessness and starvation.

There were no social welfare programs providing a safety net for workers or their families. A lack of healthcare meant poor people (and wealthier folks) self-medicated with laudanum, a mixture of opium and alcohol. It was as addictive as OxyContin and as deadly. Accidental or intentional overdoses ended the physical and emotional pain of those overcome by despair.

Living conditions were horrible. Entire families were crammed into squalid tenements, not much bigger than today’s efficiency apartments. When New York City required a specific amount of square footage per adult tenant, landlords gamed the system by building tenements with 15-foot and 20-foot ceilings, counting all that air space in the square footage calculations.

In the face of these obvious inequities, politicians decided anarchism was the real threat. They used a divide and conquer strategy to pit native born against immigrant workers to protect the privileges of the wealthiest one percent. Anarchists railed against landlords, factory bosses, cops, and judges as the representatives who enforced the capitalist system.

The slow pace of change eventually caused a split in the ranks of anarchists. Non-violent sorts like Kropotkin were optimists who believed that capitalism would collapse under the weight of its rottenness. A small offshoot advocated a violent overthrow of the capitalist system.

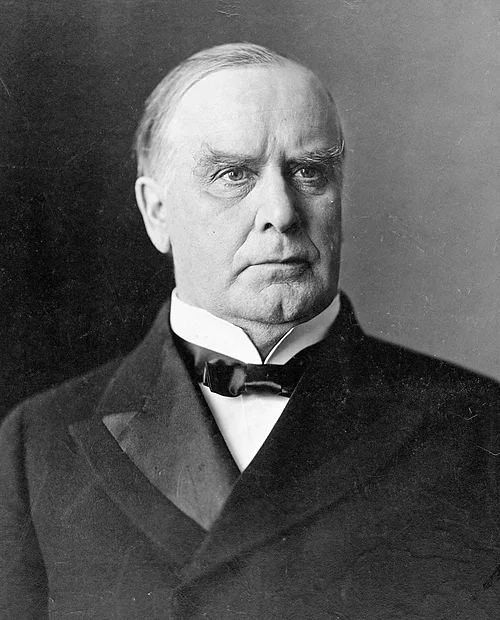

Political assassinations became popular. In 1878, the kings of Spain and Italy survived assassination attempts and Kaiser Wilhelm I survived two attempts. In 1898, Empress Elisabeth of Austria was killed by a knife-wielding nut. In 1901, President William McKinley was assassinated in Buffalo, New York. (Have any presidents visited Buffalo since?)

President William McKinley

Anarchism was never an organized political movement. It was the philosophical meanderings of individuals who felt that they were not winners in the political and economic system of their day. The assassins tended to work alone because they were radicalized privately by what they read in books and political pamphlets.

Anarchism lost its appeal in the U.S. when progressive politicians began enacting laws that protected workers (but not immigrants). In Europe, anarchism became irrelevant when the old socio-economic system was destroyed by World War I.

The modern equivalent of anarchism is the antifa (anti-fascist) philosophy. Antifa advocates tend to be educated and middle class. Some suffer white guilt like Kropotkin and long for an indefinable social justice. All come from families who feel squeezed by the current system in which they will never attain the wealth of an IT billionaire but could easily slide down into poverty.

Like the anarchists before them, antifa is not an organized political movement. Also like the anarchists, most are non-violent with a sprinkling of violent actors. As a result, this new Gilded Age will also be marred by political assassinations committed by lone wolves radicalized by what they read and see on social media. The current government will overreact by openly siding with the billionaires whose money got them elected and passing laws that protect their privileges.

Eventually, the level of inequities will become so outrageous that a new progressive era will usher in a new round of social justice legislation to make capitalism feel less predatory. Or we’ll destroy the current system with another world war. Then a new cycle will start and a new version of anarchism and antifa will emerge.

For a more in-depth look at how the original Gilded Age mirrors today’s world, including the similarities of anarchism and antifa, read The Proud Tower, by Barbara W. Tuchman (1966).

If you would like Norma’s blog sent to your inbox, we invite you sign up by clicking here! And we will see you next time!

And be sure to follow Norma on LinkedIn