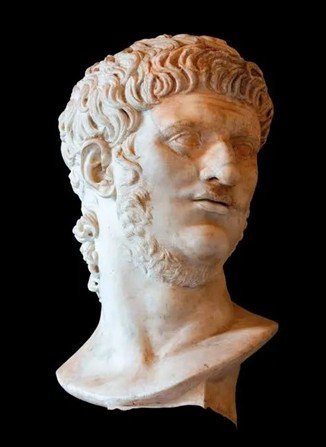

Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus was born in 37 AD to Agrippina the Younger and Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. Daddy is irrelevant since he ever-so-coincidentally died when his son was three years old. Mommy was a granddaughter of Emperor Augustus and sister to Caligula.

In ancient Rome, ambitious women used ruthless cunning and sex to get what they wanted since they had no legal rights. Agrippina was a master of both. She decided that her son should become emperor, but there was a hindrance. Her uncle Claudius was emperor and he already had a son. These impediments were a mere speed bump for her.

First, Agrippina arranged for Claudius’ wife to be executed for adultery. Then she convinced Claudius to pressure the Senate into changing the incest laws so that she could marry her uncle. Next, she had her son designated as the spare heir with the adopted name of Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus. Having served his purpose, Claudius was poisoned by Agrippina. Disposing of Claudius’ son wasn’t even a speed bump.

In 54 AD, Nero was declared emperor and Agrippina arranged his marriage to Claudius’ daughter, Octavia. Agrippina was an acute political operative who had a sense of how far she could push her cruelty without causing a fatal backlash. Nero learned only to emulate her cruelty.

As a teenager, he liked to disguise himself as a slave and wander the streets of Rome with friends, visiting brothels, shoplifting, and assaulting bystanders. His viciousness was tolerated because of his mother’s social and political influence. When his identity leaked to the public, copycat attacks on distinguished people increased. The rule of law slowly died as the emperor engaged in criminal behavior.

The problem with bullies like Nero is that he was a physical coward. He could dish it out; but he couldn’t take it. When Senator Julius Montano was attacked in the street, he fought back instinctively and punched Nero. Montano immediately apologized when he recognized the emperor, but Nero deemed the apology a slur and forced Montano to commit suicide. After that Nero always surrounded himself with soldiers and gladiators who protected him in the street brawls.

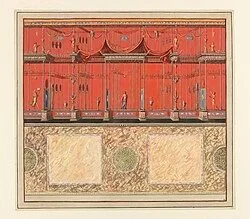

Nero may have been a coward but he loved watching violence. In his day, theater performances were often disrupted by rival gangs who supported different dance troupes. (A modern equivalent is soccer club “ultra” fans who attend games solely to start drunken brawls in the stands. Ultras are criminally prosecuted and usually banned for life from games.) Nero waived legal penalties for hooliganism and even offered prizes to the gangs. He often hid in the shadows, watching the fights. Eventually, public complaints about the violence forced Nero to station troops in theatres to keep the peace.

Nero’s attacks on the rule of law weren’t limited to hooliganism on the streets or in the theaters. He had the Senate appoint him as consul even though as emperor, he couldn’t legally serve as a consul. He used his consulship to protect a serial criminal and murderer named Publius Celer. Nero couldn’t simply pardon Celer, since the crimes weren’t committed in his province, but he ensured the court case dragged on long enough for Celer to die of natural causes. Tacitus doesn’t give a reason why Nero protected Celer but there is a hint of one crook protecting another.

Nero’s flood-the-zone approach to lawlessness was enabled by the supposedly independent Senate. Senators were wealthy and often came from aristocratic families, but that could not save them if Nero decided they were a threat to him. Besides, with corruption beginning at the top and the rule of law being ignored, nobody’s property or person was safe, so each Senator was busy grabbing what they could.

The fighting in the top 1% of society didn’t bother most people initially. They cared more about economic issues, like taxes. Tax collection was delegated to third parties who paid for a license and guaranteed a fixed amount of taxes were paid to the national treasury. The tax collectors could levy additional fees and tax amounts without any governmental oversight. Even people bad at math can see the scope for corruption.

Private tax collectors managed to climb the social and income scale almost as fast as modern tech bros, leaving a trail of financial ruin in their wake. In 58 AD, Nero decided to win public acclaim by abolishing all taxes. At that point, the Senate invited him for a chat where they flattered him for his noble generosity before explaining that an empire without revenue is doomed. Nero agreed to make tax collection fairer by setting maximums on tax rates and limiting the extra fees charged by tax collectors. Public announcements of the new limits can be seen on surviving monuments.

After this popular triumph, Nero reverted to being a selfish, greedy nepo baby. In 59 AD, he orchestrated the murder of his mother, removing the only restraint on his paranoia and megalomania. Free to live as he wanted, he decided he wanted to be a charioteer. Then he wanted to be a musician and began playing the lyre. He also declared himself a poet.

To showcase his talents, he created the Youth Games. The games were held in a newly built district consisting of brothels and taverns. He dished out money to ordinary people who could only spend it in his new redlight district. At later games, the Senate cut to the chase by offering Nero the first prize and creating awards to feed his ego.

None of it was enough. He had Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli) renamed after himself. He surrounded himself with yes-men like Tingellinus who claimed Nero was loved and admired. Tingellinus also convinced Nero to banish or murder anyone who threatened Tingellinus’ influence and power.

But everyone was becoming bored with Nero’s erratic antics. Rumors circulated that attendees were bored by his performances and that privately senators and aristocrats mocked him.

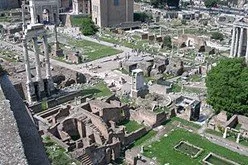

Then a fire burned Rome in 64 AD. It spread rapidly through narrow, twisty streets lined with wooden buildings. Gangs of looters prevented people from fighting the fire. As the city burned, a second fire started on the estate of Tingellinus. When the fires finally burned out, three districts were levelled, seven were barely habitable and only four districts were intact.

Nero immediately decided to build a Domus Aurea (Golden House) on the levelled districts. He bragged about marble floors, gold trimmings, and lavish murals at a time when most Roman citizens were homeless and starving. He was shocked to learn they were angry, so he ordered food to be distributed to buy their goodwill.

It wasn’t enough. Rumors circulated that Nero was playing his lyre while the city burned, or that he had started the fire so that he could steal the land to build his gilded palace. Popular opinion swung completely against him. For years, ordinary people had witnessed his excesses, thinking it didn’t affect them. But as the rule of law was hollowed out, corruption trickled down from the top 1%, gutting government services that could have assisted in rebuilding Rome.

Nero got his Golden House (parts of which have been excavated in recent years) but he didn’t get to enjoy it. In 68 AD, to avoid assassination, Nero committed suicide, abandoned and loathed by everyone. His gruesome sidekick, Tingellinus was forced to commit suicide in 69 AD.

Today we may debate whether Nero was a sociopath or a psychopath; he was certainly a mass murderer. His reign highlights how corruption at the top undermines the rule of law and quickly destroys society because no one’s property or person is safe from the criminals. His name survives as the Italian word for “black”.

This account of Nero comes from The Annals of Imperial Rome, by the historian Tacitus.